|

|

|

Tanzania, Inside Information

You

can�t get much deeper inside Tanzania than with Roland Purcell, an escaped

auctioneer from Sotheby�s who pitched his first camp closer to the Congo than

the nearest road in Tanzania, and did so with custom tents befitting a Sultan. When

Purcell led me across a vast golden flood plain in a remote park called Katavi, I was

convinced I could perceive the curvature of the earth. As he poured wine on the first night, he declared, �There�s not

another dinner party for a million square miles.� You

can�t get much deeper inside Tanzania than with Roland Purcell, an escaped

auctioneer from Sotheby�s who pitched his first camp closer to the Congo than

the nearest road in Tanzania, and did so with custom tents befitting a Sultan. When

Purcell led me across a vast golden flood plain in a remote park called Katavi, I was

convinced I could perceive the curvature of the earth. As he poured wine on the first night, he declared, �There�s not

another dinner party for a million square miles.�

Katavi National Park is far west of the

Selous Reserve, even beyond Ruaha- sacred names to aficionados who eschew

Tanzania�s Northern Circuit (including Ngorongoro Crater;) tamed by

popularity. I will see no minivans in Katavi, no other people, hear no pundits.

The lethal drip of CNN has ceased. At night, silence can be as great as the wide

world, broken by the occasional yip of hyena, the crackle of the campfire, and

stories whispered in an intimate tone, as if we were in a vast theater. Katavi National Park is far west of the

Selous Reserve, even beyond Ruaha- sacred names to aficionados who eschew

Tanzania�s Northern Circuit (including Ngorongoro Crater;) tamed by

popularity. I will see no minivans in Katavi, no other people, hear no pundits.

The lethal drip of CNN has ceased. At night, silence can be as great as the wide

world, broken by the occasional yip of hyena, the crackle of the campfire, and

stories whispered in an intimate tone, as if we were in a vast theater.

Only

in undisturbed pockets such as this can modern travelers recapture what drew

explorers and misfits like me to Africa in the first place. �It�s never to late to have a happy childhood,� notes the Purcells�

Greystoke brochure, and here the herds are wild enough to rekindle primeval

dreams. Beyond hyperbole, you simply can�t walk in most national parks, and

there is nothing in the world like walking in Africa. Australia has its

walkabouts, the landscapes of Europe are equally beautiful to behold, and I can

clear the cobwebs from my eyes in Manhattan�s Riverside Park. But on this

continent where our kind first began to walk upright on two legs, putting one

foot in front of the other can transport you back to these roots. Perhaps this

is the reason many people feel a surprising instant kinship with Africa; as

Karen Blixen wrote in Out of Africa, �Here I am where I ought to be.�

The

landscape we traversed lies on the eastern side of Lake Tanganyika, well south

of the equator but scarcely a hand axe throw east of 30 degrees longitude. A GPS

cannot impart the essential, that here on the edge of the Great Rift Valley you

can sense your position with regard to the Universe. There are visceral

reminders of ancient tensions between predator and prey, and the timeless appeal

of being nomadic. Purcell satisfies this wanderlust with a mobile camp being set

up 8 miles ahead of us.

Human

evolution, clouded by the wooly debates of fossil finders, becomes as clear as

the water in the lake to our west, and just as deep. The visibility of the lake,

it should be said, diminishes as you go deeper.

To confirm human kinship with apes, look a chimp in the eye;

Roland Purcell�s Mahale Mountain Camp is the perfect place to do this. DNA evidence suggests

chimps are our closest relatives among the apish primates, and there are also

convincing behavioral clues: males will drum the ground and scream when trying

to establish dominance, and chimps are the only animals apart from us that

recognize and study themselves in a mirror.

To confirm human kinship with apes, look a chimp in the eye;

Roland Purcell�s Mahale Mountain Camp is the perfect place to do this. DNA evidence suggests

chimps are our closest relatives among the apish primates, and there are also

convincing behavioral clues: males will drum the ground and scream when trying

to establish dominance, and chimps are the only animals apart from us that

recognize and study themselves in a mirror.

For

the nitty gritty science and insights of Stephen Jay Gould and Meave Leakey,

check your local library for a copy or order The

Hominid Gang, Behind the Scenes in the Search for Human Origins

Lake

Tanganyika has been sounded to 4,710 feet. Formed over three million years old,

it does not compete with Lake Victoria when seen on a map. Victoria is commonly

described as Africa�s largest lake, and by surface area, it is, covering an

area about the size of the state of Maine. But Lake Victoria is shallow, nowhere

deeper than 300 feet. By volume,

Lake Tanganyika is eight times larger, and it is the world�s longest

freshwater lake, stretching 420 miles north to south. Geysers that warm these waters to 86 degrees originate from a lake bottom

pulled below sea level by the shifting tectonics that created the Great Rift

Valley, a scar that stretches from the Red Sea to Mozambique and is visible from

the moon.

On

the eastern side of the lake, in the forests of the Mahale Mountains, are many

primates, including chimpanzees, red colobus monkeys, and yellow baboon that

dine on some of the 198 species of plants. It is an ecosystem more akin to the

range of mountain gorillas and other primates to the north, in Rwanda, Uganda,

and that evolutionary incubator formerly known as Zaire. The Rift split ancient

ape environments all along the heart of Africa, where you find dense forests,

including the notorious Impenetrable, adjacent to savannahs favored by antelope

and other plains game.

In

such a savannah it seems prudent to hunt on foot. Trees are few and potential

meals are fleet of foot, best killed by strategies honed in predators that do

not take kindly to scavengers. Walking

in the grasses of Katavi, Roland points out three lionesses, their blonde coats

exactly the same hue as the grass. Only the red of their bloody meal makes them

visible. �Let�s move downwind and give them a wide berth,� he whispers;

�There may not be enough to go around.�

I

went to Katavi in early October, during a drought exacerbated by rains too brief

and too late, three seasons in a row. Before this, the endless rains of El Nino

had flooded the area, washing out every second-rate bridge between here and

Nanyuki. Waters rose half way up to the branch level of fish eagles that now

watch over browned catfish, basted in a thin layer of mud, baked by the African

sun. I�m reminded of dinners in China when fish are steamed with a towel

around their head to create a strange sort of moveable feast; these cooked

catfish are relatively fresh since they too still flop.

Everything

that once thrived in this former river has come together in the only water that

remains, parched and evaporated down to a few mud holes edged by polygon cracks.

A strange sedimentary formation, dotted with red eyes, turns out to be a pod of

hippo. Packed together and oozing pink, their glands secret a rosy fluid to

protect them from sunburn, deemed �sweating blood,� closer to the truth than

any euphemism deserves to be. Without

rain, in a few weeks the hippo will die, because their bodies are so adapted to

the life that water provides them. Hippo spend up to 18 hours a day submerged,

to keep cool and minimize heat lost. Water

also makes buoyant a body that can weigh up to 7,000 pounds in an adult male,

rivaling the African elephant for weight. Marooned

like this they are weary and therefore vulnerable to predators, including humans

who eat their meat. Everything

that once thrived in this former river has come together in the only water that

remains, parched and evaporated down to a few mud holes edged by polygon cracks.

A strange sedimentary formation, dotted with red eyes, turns out to be a pod of

hippo. Packed together and oozing pink, their glands secret a rosy fluid to

protect them from sunburn, deemed �sweating blood,� closer to the truth than

any euphemism deserves to be. Without

rain, in a few weeks the hippo will die, because their bodies are so adapted to

the life that water provides them. Hippo spend up to 18 hours a day submerged,

to keep cool and minimize heat lost. Water

also makes buoyant a body that can weigh up to 7,000 pounds in an adult male,

rivaling the African elephant for weight. Marooned

like this they are weary and therefore vulnerable to predators, including humans

who eat their meat.

At

another mud hole crocodile lay alongside each other, imitating tree trunks with

interesting bark. One by one

nictitating membranes slide down to permit a glimpse of us, but the fire has

gone from their eyes, glossy with the bleary look of a drunk. Whether warm-blooded or cold, animals can react to stress just as

individually as human personalities do, with unpredictable paths of crankiness

or violence or defeatism. A drought

brings about an edge to behavior, but fortunately for observers like us, safe in

a Land Rover, this kind of pressure also induces a sad and listless fatigue. As

long as we kept our distance, they saved their energy.

On

foot we walked toward the only water to be had under these conditions, a spring

fed by underground rivers. By the time we arrive at our fly camp, a herd of Cape

buffalo dominate the nearby spring, keeping topi and other antelope waiting in a

line that stretched half a mile across the grassy plains. Then a herd of

elephant appeared out of the trees behind our camp. Protectively guarding a

two-week old infant, they slowly paraded within a hundred yards of our

entourage, which included the Purcells 3 year-old son Wolfe. The elephants

lifted  their trunks to smell us, and Zoe Purcell whispered to her son to please

keep very quiet and still so as to not make the elephants fear for their baby. Five

minutes later the elephants had overtaken the water source, mostly by simply

arriving and announcing their size,

although a young bull learning how to be macho seem to make a game out of

chasing other creatures away. Buffalo looked back towards us with their

characteristic expression of dismay, perhaps to see if any more elephants were

arriving from our neck of the woods. Fate might suggest they should thank the

elephant for displacing them. Two buffalo were stuck in the mud near the spring

and their struggles had only lodged them more firmly. �We�ve encountered

this before,� Roland explained; �Unfortunately if you try to save them, the

trauma of tying a rope around their boss and pulling them out by vehicle will

probably kill them, as well as disturb the rest of the animals. And put us in

danger.� With guilt I stared at my glass of fresh cool bottled water, half

full. their trunks to smell us, and Zoe Purcell whispered to her son to please

keep very quiet and still so as to not make the elephants fear for their baby. Five

minutes later the elephants had overtaken the water source, mostly by simply

arriving and announcing their size,

although a young bull learning how to be macho seem to make a game out of

chasing other creatures away. Buffalo looked back towards us with their

characteristic expression of dismay, perhaps to see if any more elephants were

arriving from our neck of the woods. Fate might suggest they should thank the

elephant for displacing them. Two buffalo were stuck in the mud near the spring

and their struggles had only lodged them more firmly. �We�ve encountered

this before,� Roland explained; �Unfortunately if you try to save them, the

trauma of tying a rope around their boss and pulling them out by vehicle will

probably kill them, as well as disturb the rest of the animals. And put us in

danger.� With guilt I stared at my glass of fresh cool bottled water, half

full.

For

the rest of the afternoon we sat enthralled for hours, as if part of a National

Geographic centerfold, witness to a rare Eden that was becoming rarer by the

minute. The interactions of the elephant were enhanced by the presence of

Daniella Blatiler, formerly with Abu Camp in Botswana, and an expert on

elephants. When an Abu Camp staff

worker was killed by one of the �tame� elephants last year, Daniella left to

become camp manager at Katavi.

The

scenes before us unfolded dramatically as if already edited for television.

There was no down time because we were sitting outside, beneath the trees,

within ear shot, and part of this, rather than glimpsing something briefly from

a vehicle then moving on, and because this was Katavi. Heaven and hell meet here

regularly. My heart that had felt heavy from the certain death that looms is

promptly lifted by the sight of dainty zebra, only weeks old, and hundreds of

delicate topi antelope, dancing alongside their mothers. The timing of their

birth is this year a gamble, since they are weaned only when the rains arrive,

which will provide their first taste of green grass. Meanwhile their mothers

continue to nurse them as their own bodies lack for sustenance during the

drought.

The

sky is cloudless, the grass parched yellow, which becomes that classic

Kodachrome gold at sundown. At dusk the hyena begin to arrive, surveying the

herd for the young and weak, the injured, the stuck in the mud. Zoe Purcell

shines a flash light out onto the plains, and the eyes of three hyena shine

back. They promptly disappear as the hyena saunter with their wicked he-hee-hee,

like teenage girls on their way to a verboten party.

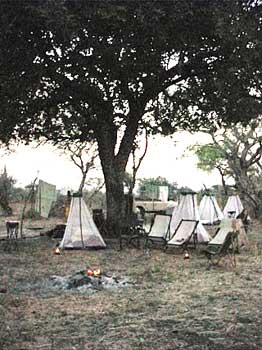

I sleep in a bedroll beneath a

mosquito net propped up by a single pole. A lantern is positioned by each

bedroll, and a campfire burns for much of the night, its mission to discourage

carnivores from finding us more tempting that the feast laid out for them. Well

before dawn, when the stars are still visible in the sky, it takes me what seems

like forever, perhaps 20 minutes, to screw up my courage to emerge from the

superficial safety of the net to stoke the fire. I reckon the chimps at Mahale might be slightly wiser than we Homo

sapiens sapiens. They sleep high in the trees, on a bed of leaves. I sleep in a bedroll beneath a

mosquito net propped up by a single pole. A lantern is positioned by each

bedroll, and a campfire burns for much of the night, its mission to discourage

carnivores from finding us more tempting that the feast laid out for them. Well

before dawn, when the stars are still visible in the sky, it takes me what seems

like forever, perhaps 20 minutes, to screw up my courage to emerge from the

superficial safety of the net to stoke the fire. I reckon the chimps at Mahale might be slightly wiser than we Homo

sapiens sapiens. They sleep high in the trees, on a bed of leaves.

Roland

Purcell tells me he plans to build a tree house in the forest canopy at

Mahale, so that guests can get close to that experience. I�ll take

a tent beneath the borassus palms, thank you, to hear the waters of Lake Tanganyika lap at the shore.

The

cost of chartering a plane to this remote area of Tanzania has been an effective

filter.Previous guests have

included members of the New York Explorer�s Club on a private jet tour of

Africa, Microsoft chairman Bill Gates, and a group of Texans (with slightly

older money) whose leader declared the mission statement in a dinner toast:

�Rape, riot and revolution! May prostitution prosper, and son of a bitch

become a household word!�

�I

ran to my tent to jot it down,� says Purcell, such

a wit in his own write that more than once I felt I was walking with Michael

Palin.

Both

the Mahale and Katavi Camps have only 6 tents, which means 12 visitors maximum.

(You can have a group of 24 and dosey-doe.) Both camps are disassembled during

the rainy seasons, normally between mid-October and mid-December, and again

mid-February to May, and there is an extra charge for fly camps.

For

information about booking the Katavi or Mahale Camps, Contact Delta

|